Originally written June 18, 2009

In the mid-1990’s there was a commercial for ESPN Sunday Night Baseball in which a Chicago Cubs bobblehead doll nodded its head repeating “This is our year! We can’t be beat!” As it said this, the doll slowly grew a beard and became covered with cobwebs. At the time I thought this was funny, but being that I was young and not particularly well-versed in Cubs history, I didn’t quite understand the depths of why it was so funny or what it truly meant to watch the Cubbies.

There are, to me, few immutable truths or superstitions that are worth relying on in professional sports. Curses, good luck, bad luck, lucky socks, lucky jockstraps, rubbing your bats with fruit, wearing the same uniforms, eating the same pregame meal, velcroing and de-velcroing your batting glove the exact same number of times before each pitch – it’s all complete lunacy. None of it is real, none of it exists, it’s all in your head.

Except one.

There is one superstition that I believe wholeheartedly without any cold data or rational reason.

“They are the Chicago Cubs.”

They’re the Cubs. They’re cursed. This is not their year. Next year will not be their year. In fact, I’m fairly certain that it will never be their year. Not once in the past 101 years have the Chicago Cubs won the World Series.

I haven’t found a Z-Score to determine the statistical significance of how unlikely it was for the Cubs to go more than a century without winning a championship, but given that there are now 30 teams in Major League Baseball, and that for the first 54 years of this streak there were only 16 teams, and if we assume that all things being equal, the Cubs should have made a World Series appearance at least once every eight years as there were only eight teams in the National League until 1962, and also assume they had a 50% chance of winning each of those World Series, well, it seems particularly unlikely that this one baseball team could go more than a century without winning a World Series.

It seems likely that this series of events would happen – all things being equal – less than five percent of the time. From this I can only assume that there is, in fact, a statistically significant bias that is causing the Cubs to have not won a championship. There must be some reason. And so, until it is determined that there is no reason, or the Cubs somehow manage to prove me wrong, I will stick with my belief that the Chicago Cubs will never win the World Series.

Because they are the Chicago Cubs.

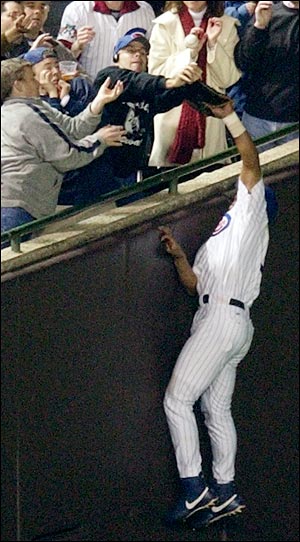

Of course, I’m sure there are legions of Cubbies fans ready to prove me wrong on this count. What evidence they have to back themselves up I couldn’t tell you. There’s 101 years of evidence that seem fairly clear cut to me. And ineptitude isn’t the only reason as Wrigleyville has suffered the most disastrous close calls this side of Fenway, such as the black cat at Shea Stadium in 1969, Chicago’s near-miss in 1984 or the devastating collapse of the Bartman Game in the 2003 NLCS.

That last one I remember extremely vividly as I was in my second month at Northwestern University when the collapse occurred. Of course, as Frou Frou might have put it, there’s beauty in the breakdown. Watching the Cubs fall apart just five outs from a World Series berth on Alex Gonzalez’s booted double-play ball and the interference on a foul pop fly down the left field line to Moises Alou, which was muffed by lifelong Cubs fan Steve Bartman, was the way the course of events were supposed to run. Because the Cubs will never win the World Series.

It was life. And in a cruel way, it was beautiful.

I pulled myself down to Sheffield and Waveland Avenues to be a part of the crowd for Game 7, hoping to witness the explosion in Wrigleyville when the Cubs made their first World Series appearance in 58 years. Alas, a rally by the Marlins, who pulled off the upset, meant it was not meant to be. The Fish would go on to an unlikely Championship that year – which I predicted a month earlier, just ask Luisa – and the Cubbies stayed home, wallowing in misery as the bad century continued its march.

I actually attended my first game at Wrigley a month before it all happened on September 28, 2003, clearing up my first order of business as I began my undergraduate career in Evanston by making my first venture inside the friendly confines. That day the confines weren’t exactly friendly – or at least they weren’t comfortable. It was extremely chilly, something that could be said 10 months out of the year in Chicago, and with the Cubs having clinched the 2003 NL Central Division title by sweeping the Pirates in a doubleheader a day earlier, this regular season finale was entirely meaningless.

I got my ticket through Northwestern as this was considered one of the New Student Week activities where you were encouraged to make friends by doing random activities with hundreds people you’ve never met before. While, at that point, I had made a few friends at school, it was still that nebulous period freshman year is heir to – a semester of eating, drinking and socializing with dozens of people you don’t know and who you aren’t sure are your real friends. Eventually, most people find their way – and their friends – and I certainly did that, but it hadn’t happened yet. I went to the game on my own, picking up my ticket at the technical institute and then following the crowd to the Noyes L stop.

Wrigley Field sits at the Addison stop on the Red Line and as the train pulled in, the conductor announced, “This stop, Addison – Wrigley Field, home of the 2003 World Series Champion Chicago Cubs.” Not surprisingly, cheers rang out as I headed out of the station and by the numerous ticket brokers trying to pawn off their last ducats outside the stadium. There are dozens of them. Ticket scalping is a common sight at every stadium, but Wrigley has an abundance of them. If a Cubs game appears to be sold out, have no fear, you will still be able to find a ticket. If you have overwhelming demands such as “being in your seat by first pitch”, you may pay an arm and a leg for one. However, if you wait until the start of the first inning, the prices drop quickly.

Wrigley is a building that looks as old as it is. The exterior is covered with paint that is constantly crackling or peeling, the green roof on top seems lower to the ground than it actually is and the big red marquee behind home plate looks like something out of a Charlie Chaplin film. But I say these things not out of skepticism, but adoration. Where Wrigley lags behind Fenway in terms of city-necessitated quirks or championships it makes up for with an unbelievable amount of charm.

Wrigley’s aged appearance has a friendly appeal that makes it feel warm, even if the weather almost never is. There are moments and days when the weather at Wrigley is wonderful, but they are impossible to predict and disappear as quickly as they come. On some days, if you’re lucky, there will actually be multiple weather patterns within the stadium, as was the case when Evan Hung and I felt 45-degree chills in the upper deck while bleacher bums went shirtless because of the oppressive sun in the outfield. My sophomore year at school I went to all three games the Mets played in Chicago and found myself one night in monsoon-like conditions, the next night under clear skies and 80-degree weather, and the final day stuck in the bleachers shivering as the temperature struggled to break 40. The pain of that day was exacerbated when famed longtime Cubs fan Ronnie “Woo Woo” Wickers, a man who legendary Cubs announcer Harry Caray dubbed “Leather Lungs” for his ability to shout for hours at a time, razzed me personally in front of a crowd as I exited the stadium when the Mets fell in extra innings.

Woo Woo has become a cult hero around Wrigleyville, recognized far and wide as one of the most dedicated souls in the Windy City. Wickers has become so popular over the years that he led the crowd in “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” during the seventh-inning stretch in 2001, an honor typically reserved for local celebrities or ones who just happen to be passing through the city. Ozzie Osborne once delivered a particularly memorable – and entirely indecipherable – rendition of the tune.

Wickers actually spent most of his adult life as a night custodian at Northwestern before briefly being homeless in the late 1980s, a period during which he attended most games with donated tickets. If nothing else, this is a place where the fans appreciate the other fans. One such notable incident occurred in 2008, when the Cubs allowed someone who had actually seen them win a World Series, 104-year-old Leo Hildebrand, throw out the first pitch to a raucous ovation. Of course, this came after the Cubs front office had initially denied Hildebrand’s request and then caved to a wave of bad press.

Being razzed by Woo Woo was embarrassing and my friends mocked me on most of the ride home, but I’ve since come to view it as an honor of sorts. At the very least, whether he mocks you or not, you know Woo Woo will always be there. He, and perhaps annual disappointment for the Cubs faithful, unlike the weather, are constants around the park.

Wrigley is famed for its Ivy-covered brick outfield walls, and they are a pretty sight to see – and I imagine a painful one to experience – but this only holds true in the later months of the season. In April, the ivy is still reeling from the sub-zero Chicago winters and is a mess of brown and gray. Personally, the ivy isn’t my favorite feature in the old yard even if it is the most famous. For me the two things that truly stick out are the old timey centerfield scoreboard and the extended bleachers across Sheffield and Waveland. The scoreboard is still operated by hand and has pennants of all 16 National League teams hanging above it in division order. It doesn’t seem very far from home plate in the deceptively large building, but the only person to ever hit it, according to legend, is PGA great Sam Snead, who needed a golf ball to do it.

Beyond the scoreboard, the bleachers across the street from Wrigley are a unique characteristic of taking in the Cubs games. Like many old parks, the stadium sits in an urban area where rooftops from across the street can see into the grounds with ease. While people BBQing as they watched the games for free was a practice quietly tolerated by the Cubs for decades, enterprising landowners eventually billed bleachers on the roofs of each building to be rented out during games. Not surprisingly, this brought legal action from the ball club in 2002, with the rooftop owners eventually agree to donate a portion of their proceeds to the Cubs. Since then, the Cubs have advertised the rooftops on their website, endorsing them as “partners” with the team.

One such rooftop across Sheffield Avenue in right field is frequented by the Lakeview Baseball Club, which boasts a famous sign which says, “Eamus Catuli” or what is roughly the Latin for “Let’s Go Cubs”. While the “Catuli” literally translates to “whelp”, the Wrigley faithful have latched on to the phrase anyway, with the same rooftop also posting a sign which says “AC0064101”. AC stands for “Anno Catuli”, or “in the year of the Cub”, while the next two digits count down the years passed since a Cubs division title, with the next two counting years since a National League pennant and the last three the time passed since the Cubs last won the World Series. While division championships have become a norm in recent years, the last two numbers have only gotten larger. However, it speaks to the almost irrational pride these fans have that they would publicize their decades-long futility rather than hide it.

While I went to my fair share of games in college, I almost spent more time around Wrigley than in it. Wrigleyville is a noted weekend hot spot populated by all the Northwestern undergrads who recently turned 21 and want to feel like adults by paying for alcohol they could have gotten for free at a house or apartment party. No, these aren’t the only people drinking in Wrigleyville on a Saturday night, but you’ll almost always bump into someone you know from school if you’re in the neighborhood. While many of the bars are generic, some pay homage to the Cubs’ history, like Merkle’s, which is named for the New York Giants rookie Fred Merkle, whose famous inability to touch second base – known as Merkle’s Boner – cost the Giants the 1908 pennant, launching the Cubs to their most recent World Series title. Others are historic spots in their own right such as the Billy Goat Tavern, which just might be the root of all this pain and suffering. The Tavern’s owner, Billy Sianis supposedly was asked to leave Wrigley during the 1945 World Series because his pet billy goat had an offending odor, prompting Sianis to declare that he would curse the franchise from ever again playing in the Fall Classic.

They haven’t since.

There have been a number of attempts to shed the curse, including a recent bizarre trend of leaving dead goat carcasses hanging from the statue of Cubs announcer Harry Caray outside the stadium. As of yet, these attempts have been unsuccessful. But the first day I was there, the one sense I got more than any other from the fans around me was, certainly, the curse of the Billy Goat wouldn’t be hanging around for much longer. With the Cubs winning a division title and earning a postseason berth, surely this was their year. Of course it wasn’t their year. They are the Cubs after all, but as I soaked in my first day at the legendary ballpark, the fans all seemed carefree, safe in the knowledge that the Central division champs were one step closer to ending a century of heartbreak.

After the first few innings of watching the game by myself, something I don’t particularly enjoy, I was lucky enough to happen upon Adam Rowings, who had been one of a group of Northwestern freshman I went camping with in Minnesota before school started. I would watch the rest of the game, an unremarkable 3-2 win for the Bucs with Adam, a lifelong Cubs fan, who I imagine was also certain Chicago’s World Series drought was set to end that fall. Of course, it was not meant to be, as Steve Bartman’s misfortune became the misfortune of all the Cubs faithful.

Near the end of my college career, I made a point to squeeze in one last game at Wrigley, and was lucky in that my roommate, Abe, and friend David Morrison, were both Marlins fans willing to see a game on May 30, 2007 when the Fish were in town. The primary draw for me, aside from the sheer joy of watching a game in that building, was that it was Alfonso Soriano bobblehead day. The three of us threw caution to the wind and bought pricier seats near the field level. The upshot of this was a great view of the game on a picture perfect night. The downside was nearly three years later, Dave still owes me $50 for the ticket. Dave, however, was my co-beat writer at the Daily Northwestern for Women’s Tennis and Women’s Basketball. Considering Dave probably spent more time with me than anyone who didn’t live with me or date me, I feel like he’s had enough exposure to my neuroses that I should give him a break.

Abe and Dave left happy as the Marlins beat the Cubs up that night. Dan Uggla launched two home runs while Miguel Cabrera and Josh Willingham added longballs of their own en route to a 9-0 thumping. The Cubs had fallen quite a bit since losing the NLCS to these same Marlins four years earlier. Evidently, after another brush with greatness, the Cubs were left to realize that the curse still lives.

In a desperate bid to end the scourge of the Billy Goat, the Bartman baseball was later bought at auction by Harry Caray’s restaurant and blown up in front of an approving crowd. The remains were then boiled with the steam being captured, distilled, and used in a pasta sauce, which would later be served at the restaurant. The proceeds from this dish were donated to the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the same charity that Bartman himself suggested any Marlins fans looking to send him gifts donate their money to.

In theory, the explosion and digestion of the ball was expected to overturn the Curse of the Billy Goat once and for all. How permanently making a symbol of your eternal pain part of you overturns said pain is a concept well beyond me, but at this point I don’t blame Cubs fans for trying everything in the book. No doubt, they are a dedicated lot – they have to be to still love this team without a title in more than a lifetime. But if going to numerous games at the friendly confines and living among Cubs fans for four years taught me anything, it’s that they shouldn’t be worried about the heartbreak of the past. Steve Bartman and every Billy Goat they can find are of no concern to the mighty Catuli and their fans. They are not overwhelmed or beleaguered by the curses, or their title drought. Nowadays they are supremely confident rather than dwelling on their struggles.

After all, as they’ll tell you every April, this is their year.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment